Rice is a foundational ingredient of Thai cuisine, as it is for many other Asian cuisines. And over the years I’ve gotten a lot of questions about different types of rice: jasmine rice, basmati rice, short grain rice. How are they different? When should you use which rice? And do they need to be cooked differently? So in this article I want to demystify all of that and help you make the right rice decision for your next meal!

I’m going to talk about the 3 most common types of rice used in Asia: Japanese short and medium grain rice (aka "sushi rice"), basmati rice, and jasmine rice.

Want to save this recipe?

Jump to:

- Video: Sushi, Jasmine and Basmati Rice Explained + How to Cook Them

- The 3 Types of Rice Most Commonly Eaten in Asia

- Thai People Don't Eat Only Jasmine Rice

- Appearance, Taste, and Texture Comparison

- Aroma Comparison

- What About Brown Rice?

- How to Cook Different Types of Rice

- How Much Water Do You Need To Cook Different Types of Rice?

- Useful Fact: What's the Volume of the "Rice Cup?"

- Other factors affecting the amount of water needed to cook rice

- Does the 1-Knuckle Rule Work?

- Which Type of Rice Should You Use For Which Dish?

- Come Down the Rice Rabbit Hole!

Video: Sushi, Jasmine and Basmati Rice Explained + How to Cook Them

If you prefer watching to reading, in this video I cover most of what is included in this article, but you may find the visuals of the video more helpful as they more clearly show the differences between the types of rice. The video also includes a demo for how to cook each type properly.

The 3 Types of Rice Most Commonly Eaten in Asia

Let's go through the types of rice we're going to cover here.

First is what most people call "sushi rice." There are many varieties that fall into this category, some are considered short grain and others are considered medium grain. For this article I’ll call it "sushi rice" for simplicity, but know that in addition to Japan, this is also the type of rice that’s also eaten in Korea and parts of China.

Then we have jasmine rice which is the staple rice of Southeast Asia. For our discussion jasmine rice will also represent other varieties of long grain rice that are similar but not technically jasmine. I’ll call these “jasmine adjacents,” which will also include the generic “long grain white rice” that you see in most Western grocery stores.

Finally basmati rice, the longest grain of them all, and this is the rice eaten in the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East. Like the other two this also represents the many other subtypes of basmati rice that also exist.

Thai People Don't Eat Only Jasmine Rice

There's a misconception that Thai people, and Southeast Asians in general, only eat jasmine rice, but this is not true. Thai jasmine rice or hom mali rice is the best, most prized rice of Thailand, and it is our most popular exported rice. But it is also the most expensive, which is why when you go to Thailand and you're eating at an inexpensive street-side restaurant, they're likely not using jasmine rice, but one of the many other varieties of long grain white rice that we have.

Aside from being more fragrant, Thai hom mali rice also tends to be softer and stickier than other adjacent varieties, making it not ideal for fried rice So many restaurants who make fried rice will choose another variety, such as sao hai rice, which is less soft and sticky. Or they may also do a mix of varieties.

It is worth noting that the word "jasmine rice" is not regulated. So it may say jasmine rice on the bag, but it may not be the prized jasmine hom mali rice Thailand is known for. So if you want real hom mali rice, look for the green round logo at the top of the bag in the picture above This is the government seal certifying that the rice is genuine hom mali. Now, the logo has also been known to be faked, so go with a reputable brand if you can (Royal Umbrella, Kirkland, or 3 Ladies, for example.)

Appearance, Taste, and Texture Comparison

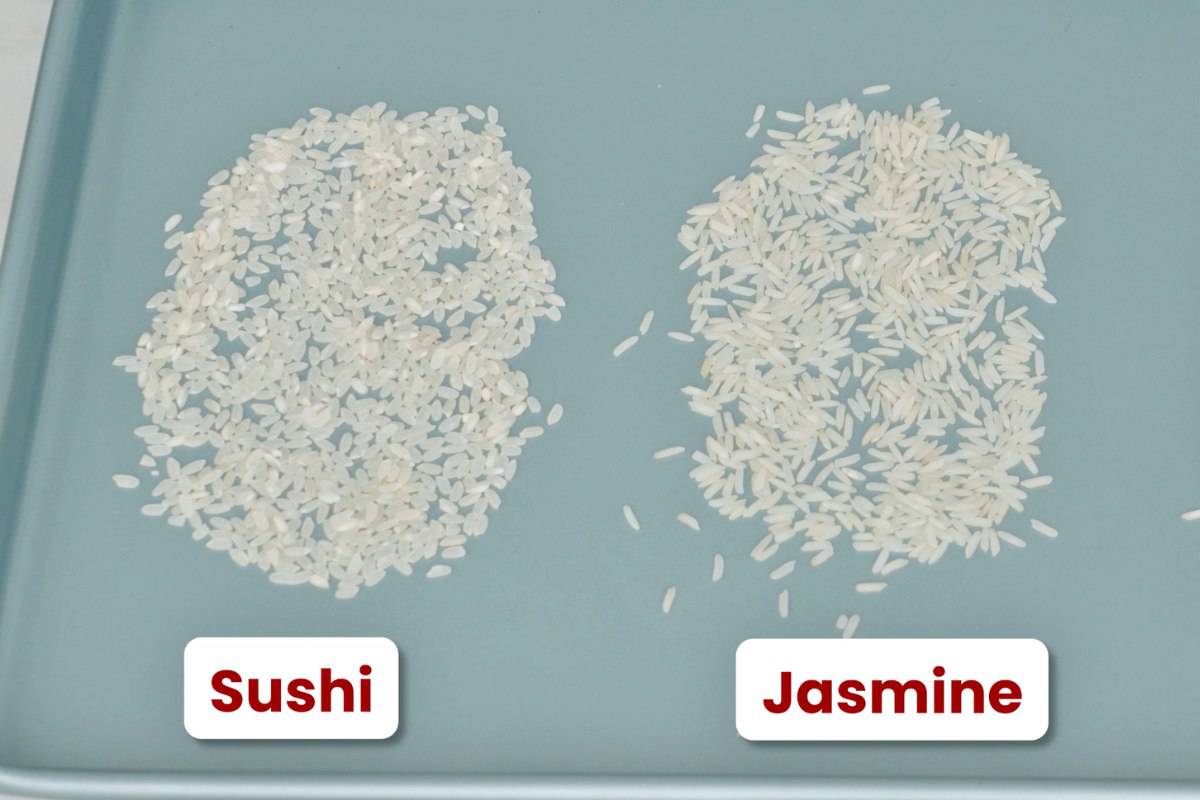

Sushi Rice

Sushi rice grains are short and chubby when compared to the other two rices, and the key feature here is that when cooked it is quite sticky. So when I try to pick it up with my hand, it sticks to my hand AND the grains stick to each other very well.

This is why it’s great for making sushi or kimbap where you want the rice to stick together - and this is why cultures that eat this kind of rice can eat it with chopsticks.

The texture, when cooked properly, is also a little bit chewy because it’s more dense than long grain rice. It is a very satisfying, toothsome texture.

Basmati Rice

On the other end of the spectrum, we’ve got basmati rice which are not sticky at all. If I pick it up with my fingers they won’t stick to my fingers AND won’t stick to each other.

The grains are very long and skinny, and this becomes even more obvious after you cook them because the grains get significantly longer but not much wider.

The texture is not chewy at all. It is tender, but there’s also a brittleness or a snappiness to it when you bite into the grains. Because they don’t stick together at all, the mouthfeel of basmati rice tends to feel a little bit drier, and this is why it is often cooked with added fat such as butter or oil.

Jasmine Rice

And in between these two extremes is jasmine rice and its adjacents. The grains are shorter and fatter than basmati, but longer and skinnier than sushi rice. It sticks together better than basmati, but not as much as sushi rice. The texture is not chewy, but compared to basmati it is softer and cushier, with a fluffier texture - though some non-jasmine varieties, such as the generic long grain white rice at Western stores, tend to be less soft. The mouthfeel of jasmine rice also feels quite moist compared to basmati and short grain.

Important: Sushi rice is NOT sticky rice.

A lot of people call sushi rice "sticky rice" because, for all intents and purposes, it IS pretty sticky. But it is not true "sticky rice". REAL sticky rice is wayyyyy stickier than this and it is technically called glutinous rice. Glutinous rice comes in both short AND long grain; the short grain is what the Japanese call mochigome or “mochi rice”, and the long grain is what Thai people call khao niew which literally means “chewy rice”.

If you want to dig deeper into sticky rice see my post on sticky rice 101, but for now just know that they cannot be used or cooked in the same way as their non-glutinous counterparts.

Aroma Comparison

There is also big a difference in the way these types of rice smell. Most known for its fragrance is Thai jasmine rice. The reason it is called jasmine rice is because of its beautiful floral aroma similar to jasmine flower. In Thai jasmine rice is called "hom mali" rice which means "fragrant of jasmine flowers." You can smell this scent even before you cook the rice!

Basmati rice is also fragrant, though the aroma is different from jasmine rice. I’d describe it as having a grassier aroma, whereas jasmine is more floral.

Sushi rice is not as fragrant as the other two. It does have that smell you associate with rice in general, but it isn't distinctly aromatic. That was one thing I immediately noticed the first time I cooked sushi rice after a lifetime of cooking jasmine!

What About Brown Rice?

So where does brown rice fit into all this? Brown rice is not another type of rice, it's just processed differently. All white rice has a brown version because white rice is simply brown rice with the bran removed.

So brown rice is going to be more fibrous, and chewier than their white counterpart, but the chew is coming from the brown bran on the outside, and not the rice on the inside. You can cook brown rice using the same method as white rice, but you’ll need a little more water and a little more time because it takes more time for the water to penetrate through the bran.

Here’s my hot tip: If you don’t like brown rice because you think it tastes like chewy twigs, try brown Thai jasmine rice; meaning real hom mali rice. It is the best tasting, softest brown rice I’ve had, and the jasmine aroma will counteract any twiggy flavour from the bran.

How to Cook Different Types of Rice

The good news is that even though they are very different, you can actually cook all 3 types of rice using this standard method of cooking rice most common in Asia. It's the simplest, it's the same method that electric rice cookers use, and I think it yields the best results.

BUT you will need different amounts of water to match the rice you're cooking, as outlined below. There are other factors that can affect how much water you need, and we’ll talk more about that in a bit, but the type of rice is by far the biggest determinant.

If you're using a rice cooker, you still need to add the correct amount of water. The rice cooker is not magic, all it's doing is stopping the cooking when all the water has been absorbed, it cannot fix dry or mushy rice. So here is a guideline for how much water you need for each type of rice.

How Much Water Do You Need To Cook Different Types of Rice?

If you're using the standard stovetop method, OR if you're using a rice cooker, here's the amount of water you need:

For sushi rice (Japanese short grain and medium grain, including US grown brands)

- You need a ratio of 1 part rice to 1 part water, by volume.

So 1 cup of rice, 1 cup of water. Whatever kind of cup, coffee cup, rice cup, measuring cup, it doesn't matter, it's all about the ratio. This ratio also seems to be quite stable between brands in my experience, but you can adjust according to your preference.

If you have a Japanese rice cooker like a Zojirushi, and you’re using the rice cup that comes with the cooker to measure your rice, you’ll notice that this ratio of water corresponds to the “white rice” line in the rice cooker, so you can go with that line to simplify. By extension, if you're cooking jasmine or basmati rice in a Japanese rice cooker, you cannot use those water lines.

For jasmine rice and its adjacents.

- You need a ratio of 1 part rice to 1¼ to 1½ parts water, depending on the variety, brand, and your preference.

If your rice cooker comes from a country that eats primarily jasmine and long grain white rice, including Thailand, Hong Kong, even US and Canada, AND if you’re using the measuring cup that came with the rice cooker to measure, you’ll notice that the water lines in these rice cooker corresponds to a ratio of 1 part rice to 1 ½ parts water.

For basmati rice

- You need a ratio of 1 part rice to 1 ¾ - 2 parts water, again depending on the variety, brand and your preference.

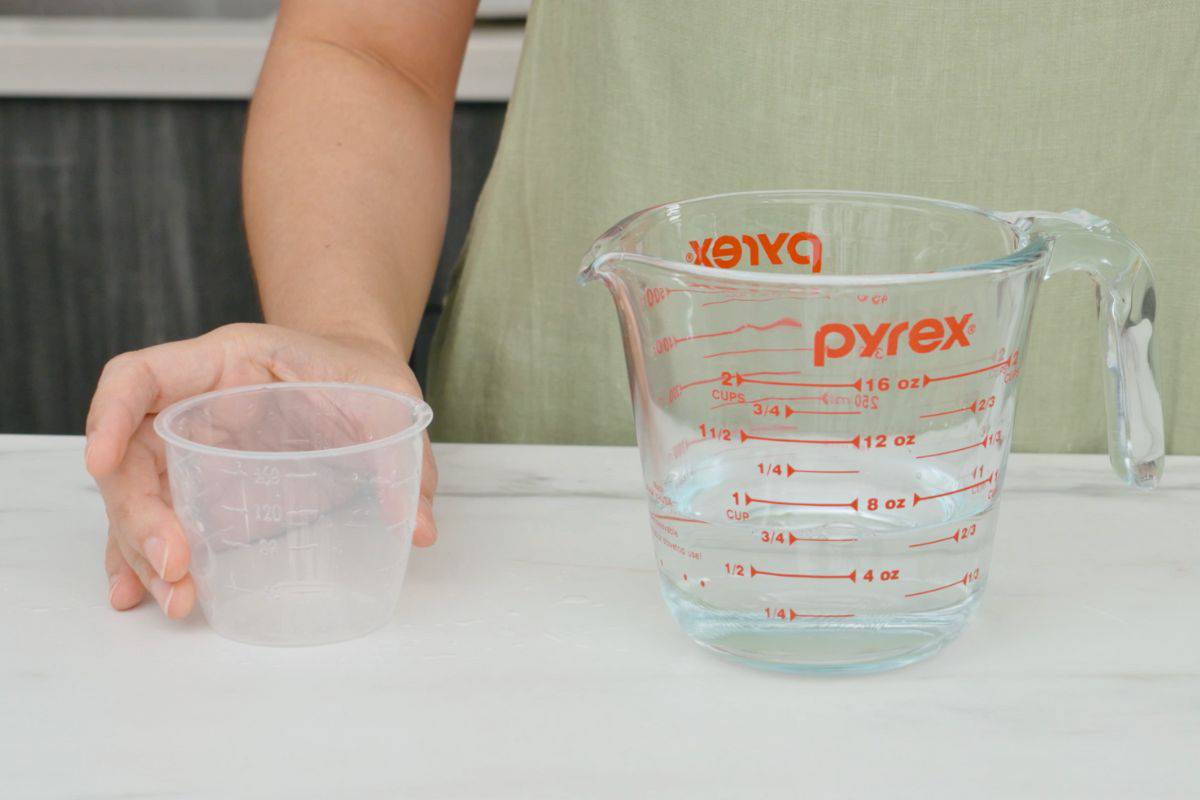

Useful Fact: What's the Volume of the "Rice Cup?"

The measuring cups that come with every rice cooker are equivalent to 180 ml or ¾ cup. Useful to remember if you ever lose the cup! I'm pretty confident that this is consistent across all brands of rice cookers, because I've used many rice cookers in my life, and I have never seen one with a different size cup. (*The Zojirushi provides an additional green cup that's 10 ml smaller, made specifically for Japanese no-rinse rice.)

The benefit of using this rice cup to measure your rice is that you can use the water lines in the rice cooker to measure the water, but ONLY IF you're using the type of rice that matches the nationality of the rice cooker. Which means...

The water lines in a Japanese rice cookers are made for Japanese rice, so it corresponds to a 1:1 rice to water ratio. And the water lines in most N. American rice cookers are made for long grain white rice (jasmine and adjacents) and it corresponds to a 1:1 ½ rice to water ratio. Do Indian rice cookers have basmati-specific water lines? Probably? Though I've never seen an Indian rice cooker before so I can't say for sure!

Other factors affecting the amount of water needed to cook rice

The ratio of water I provided is just a guideline, as there are other factors that can affect the amount of water needed, beyond the type of rice.

- The brand of rice. Even though you’re cooking the same type of rice, the specific plant varieties can be different between brands. AND the processing can most certainly be different. Rice has to be dried before it’s milled and packaged, and how LONG the rice was dried will affect how much water is required to rehydrate it in the cooking process.

So if you’re working with a new brand of rice, be aware that it may require a different amount of water than you're used to. - Evaporation during cooking. How much water you add is one thing, but how much is lost during cooking is another. This depends on how high your heat is, how wide or narrow your pot is, how tight fitting your lid is, etc. Some people leave the pot uncovered in the beginning in order to see if the rice is boiling, so they’ll lose more water that way. All these things are slightly different for everyone.

- Your preference. Some people like rice that is firmer and dryer, others prefer it softer. I always find the rice at my parents' house too soft, but that’s how they like it, and that's okay! Also, if you're going to use the rice for fried rice, you may want to add slightly less water.

Does the 1-Knuckle Rule Work?

Some of you might have been taught to cook rice by adding enough water so that it is “1 knuckle” above the rice, specifically the first knuckle of your index finger. Does this method work?

Well, it CAN work, but not always.

If you use the 1-knuckle rule, the rice to water ratio will be roughly equivalent to 1 : 1 ½ IF you're cooking at least 2 rice-cups of rice (1.5 measuring cups). So this is why it generally works for jasmine rice and its long grain white rice adjacents. And if you talk to people who follow the 1-knuckle rule, you’ll find that they are usually cooking this type of rice and cooking enough to feed a family. (I'm looking at you, my East Asian friends.)

And because jasmine rice is generally quite forgiving, meaning you can add a little more or a little less water and still have decent rice, the 1-knuckle rule seems to work for a lot of people despite different finger lengths.

But there are a few situations where the 1-knuckle rule does not work:

- If you’re using Japanese short/medium grain rice, basmati rice, or another kind of rice that takes a different ratio of water, it won't work.

- Your rice pot is not straight sided. If the pot has sloped or curved sides, like the pot of my Zojirushi rice cooker, it won't work.

- If your rice happens to be new crop, the 1-knuckle rule might produce slightly too-wet rice.

- If you're cooking a tiny bit of rice, i.e. 1 rice-cup (¾ measuring cup) or less, it will not work. These days I often cook only half a rice-cup at a time because it's the perfect amount for my son's lunch box, and using 1-knuckle would mean way too much water.

- This is obvious but it must be said: if you have unusually long or short knuckle!

Which Type of Rice Should You Use For Which Dish?

This is a important aspect of cooking with rice. You could cook the perfect rice, but if it's the wrong rice for the job, it won't be a perfect meal. We now know that there are huge differences between types of rice, so it should go without saying that they are NOT interchangeable.

Here’s my rule of thumb: You should always serve the rice that matches the cuisine. If you’re making japanese food, use Japanese rice. If you’re cooking Thai food, use jasmine rice. Indian food, basmati rice, etc.

Each country’s cuisine has been designed to pair with the rice that is local to their country. The food was not developed independent of the rice.

So if you mix and match, sometimes it might be okay, but other times it’s not. The extreme example is if you try to make sushi using basmati rice. Basmati rice will not hold together. But a more subtle example is if you try to eat a Thai green curry with basmati rice. Thai green curry, and most other Thai curries, are very thin and soupy, and if you poured it over basmati rice which doesn’t stick together at all, the rice will just turn into a soupy mess. But Thai rice with stick together enough.

Come Down the Rice Rabbit Hole!

If you're interested in learning about Thai rice, there is SO much more you can learn. So here are just a few more posts about rice, and if you're ready to get cooking, here are all of my rice-based recipes!

Nom de plume says

Awesome tutorial, Pailin!

A lifelong student of Thai cuisine, and love your explanations, recipes and overall vibe. Please keep up the good work!

On the issue of rice, i have one small contribution to make:

One other factor for figuring out the rice:water ratio is the AGEING of the rice. Typically, the basmati you get in the market is aged from a few months to a couple of years. The most prized varieties are the premium long-grain variants from Punjab state and kept in storage for ~2 years.

Those are the ones that need a 1:2 ratio.

The shorter age ones will do with the 1-knuckle rule.

The identifier is the color. The aged basmati will be a deep beige (for the dehusked variant), while the new ones will tend to be whiter

Happy to be able to contribute something to your readers